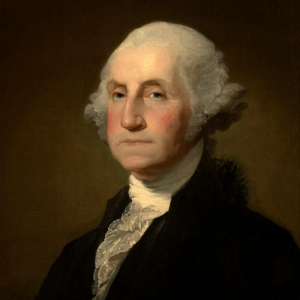

George Washington

Every third Monday in February is known to many Americans as Presidents Day (and sometimes other names). Officially, as far as the federal government is concerned, the day is “Washington’s Birthday.” This is a bit ironic considering the fact that the holiday never falls on George Washington’s actual birthday, which is February 22.

Every third Monday in February is known to many Americans as Presidents Day (and sometimes other names). Officially, as far as the federal government is concerned, the day is “Washington’s Birthday.” This is a bit ironic considering the fact that the holiday never falls on George Washington’s actual birthday, which is February 22.

Despite that, Presidents Day is a great opportunity to reflect on the life of our first president, George Washington.

George Washington, the first President of the United States, remains inarguably one of the most influential figures in American history. George Washington’s life was marked by service, sacrifice, and leadership, and it runs parallel to the birth and early struggles of the United States of America. Upon examining it, we can see a compelling narrative of dedication to the American ideals of liberty and self-governance.

The Father of Our Nation

George Washington was born on his family’s plantation in Virginia on February 22, 1732. to Augustine and Mary Ball Washington. His father, Augustine Washington, was a successful planter and also served as a justice of the county court. His mother, Mary Ball Washington, was Augustine’s second wife.

Augustine first wife, Jane Butler, died in 1729. They had two sons, Lawrence and Augustine, Jr., and a daughter named Jane. Augustine and Mary had six children—George, Elizabeth, Samuel, John Augustine, Charles, and Mildred.

George Washington never went to a university, nor did he ever receive formal education. However, he still studied and likely received private tutoring. He studied reading and writing and even trigonometry, which was necessary for his first career—surveying.

George Washington’s Family

George Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis on January 6, 1759. Martha Washington had been previously married. Her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis, died of either a heart attack or a throat infection (his cause of death is debated among historians). Martha and Daniel had four children together. Two passed away while still quite young, and the remaining two were John, nicknamed Jacky, and Martha, known as Patsy. When just 17 years old, Patsy had a seizure and died.

George and Martha Washington never had any children, and there are no known reports or records of Martha ever having a miscarriage or a child dying in an accident.

The American Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War, George Washington assumed command of the Continental Army despite not having adequate military experience. He faced a steep learning curve as he led a fledgling army against the formidable British forces, arguably the strongest military force in the world at the time.

Washington’s military career was littered with setbacks, including the loss of New York City and the surrender of For Washington. Overall, he lost more battles than he won, but his resilience and strategic acumen during the most critical aspects of the war turned the tide of the revolution.

His daring Christmas night crossing of the icy Delaware River in 1776, which led to pivotal victories at Trenton and Princeton, remains one of the most iconic moments in the entire war. Despite harsh wind and freezing snow and rain, despite being behind schedule, and despite the British and Hessian troops being aware of a possible attack, the strategy proved successful and the Battle of Trenton was a victory for the American rebels. It was also Washington’s first victory.

The victory revitalized morale among the American troops and solidified Washington’s reputation as a bold and resourceful leader.

Washington’s leadership and grit culminated in the decisive triumph at Yorktown in October 1781. With the aid of French forces, Washington secured the surrender of General Cornwallis’s army. This victory led to the peace negotiations that ended the Revolutionary War, giving the colonies independence and forever establishing George Washington as a symbol of American perseverance and ingenuity, even in the face of daunting odds.

His ability to maintain the morale of his troops, despite harsh winters, scarce resources, and a decidedly more powerful opponent, proved his unwavering commitment to the American cause of liberty. And on December 23, 1783, in a move that likely surprised most of his peers, Washington resigned his commission before Congress.

Why would he do such a thing? Because Washington wasn’t a man seeking power or even reputation. If he had different ambitions, perhaps he could have been the king of the independent colonies. Everything he did, he did for the liberty of his countrymen.

He went back home to his Mount Vernon Estate with every intention of never coming back into the limelight. (Note: George Washington’s Mount Vernon is not to be confused with a building in Barbados known as the George Washington House, where Washington allegedly stayed as a young man, but historians generally refute this claim.)

Another fun fact—in the mid-19th century, Mount Vernon was in a sorry state; funds were insufficient to maintain it properly. As a result, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association was formed to bring the estate back to its former glory and preserve it from then on. In 1960, Mount Vernon was designated as a National Historic Landmark.

The First President of the United States

As President of the United States, George Washington faced the rather monumental task of defining this new executive role in a new government. With no precedent to fall back on, his administration focused on establishing efficient governance, maintaining neutrality during international conflicts (after such a brutal war to win independence, the last thing the states needed was another conflict), and fostering economic stability through measures like Alexander Hamilton’s financial programs.

Washington’s First Inaugural Address highlighted his humility and his commitment to serving the nation. In his own words, he considered himself “unpracticed in the duties of civil administration” but was nonetheless “summoned by [his] Country, whose voice [he could] never hear but with veneration and love.”

Recognizing his own inherent weaknesses, Washington naturally did the smart thing by surrounding himself with capable people, such as Alexander Hamilton, who served as Secretary of the Treasury, and Thomas Jefferson, who was Secretary of State. They and a handful of other men were his primary advisors.

Managing debt and establishing peace were among Washington’s priorities during his first term. But Washington could only do so much. Indian wars continued in the west, political divides grew organically, and western expansion was going to be no easy task with the British, the French, and the Spanish also seeking their own interests on the continent.

But Washington had the support of the American people, including both sides of the emerging political spectrum. Despite his humble desire to relinquish what little power the president had at that time and retire permanently to Mount Vernon to live out his days, Washington was, in his words, “reluctantly drawn” to a second term. After all, the American people needed him and looked upon him, rightfully so, as a powerful yet thoughtful leader who could get the country through its turbulent infancy.

The start of Washington’s second term coincided with the beginning of the bloody French Revolution. Washington knew without a doubt that getting involved in the war would only lead to hardship for the states. He was determined to remain neutral and succeeded in keeping the country out of a potentially disastrous war.

Partisanship continued to strengthen, to Washington’s dismay, but many things improved during the second term. One of these improvements was the Spanish Empire opening the Mississippi River to American trade and so forth.

“My feelings do not permit me to suspend the deep acknowledgment of that debt of gratitude which I owe to my beloved country for the many honors it has conferred upon me,” Washington remarked in his farewell address, “still more for the steadfast confidence with which it has supported me and for the opportunities I have thence enjoyed of manifesting my inviolable attachment by services faithful and persevering, though in usefulness unequal to my zeal.”

The presidency was not an opportunity for power but an opportunity to serve the country that had given him so much.

Retirement and Legacy of George Washington

In 1797, George Washington finally retired to Mount Vernon, intent on spending his remaining years on this earth in peace. However, he continued to correspond with national leaders, offering much-needed counsel to them as the country continued to navigate its early years.

In December 1799, while overseeing the agricultural workings of his estate, Washington endured a day of snow, hail, and rain. When it was time to come in for dinner, he remained in his drenched clothes, choosing to be on time rather than dry.

He developed a sore throat before bed and during the night awoke feeling quite ill. Despite the best efforts of the family doctor, his condition worsened and Washington passed away two days later (December 14), surrounded by family, friends, and some of his enslaved houseworkers.

His body spent three days in a coffin in one of the estate’s parlors and then was placed in the family tomb on December 18.

In his will, Washington directed that all his slaves be emancipated after Martha’s death—a reflection of how his views on slavery changed throughout his life. Though limited in its scope, this act demonstrated Washington’s awareness of the contradictions between the nation’s founding ideals and the actual practices of many Americans.

Washington’s legacy has extended far, far beyond his lifetime. His leadership during the American Revolution, his role in shaping the Constitution, and his honorable presidency established enduring principles of governance and integrity.

George Washington warned against the dangers of political factions and foreign alliances, and his vision for the United States of America as a strong and independent nation that is grounded in democratic principles continues to inspire current leaders of the nation.

He inspired and united his fellow Americans on both sides of the political aisle and from diverse backgrounds. It’s no wonder George Washington is often called the “father” of our country. His life exemplified many of the ideals we all strive for in our own personal lives and in our public discourse.

Truly, there has never been a greater American Dream.